World’s oldest complete star map, lost for millennia, found inside medieval manuscript

Scholars may have just discovered a fragment of the world’s oldest complete star map.

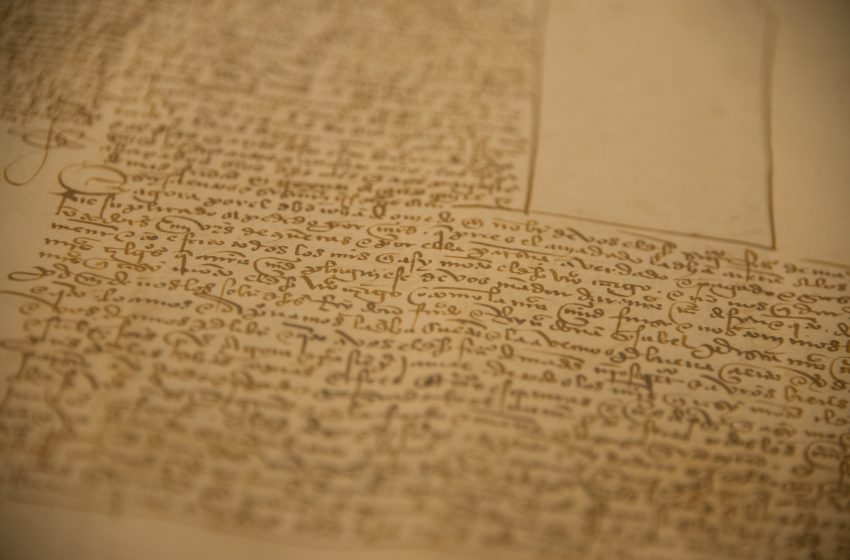

The map segment, which was found beneath the text on a sheet of medieval parchment, is thought to be a copy of the long-lost star catalog of the second century B.C. Greek astronomer Hipparchus, who made the earliest known attempt to chart the entire night sky. The fragment was concealed beneath nine leaves, or folios, of the religious Codex Climaci Rescriptus at St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula.

The codex is a palimpsest, meaning the original writings have been scraped from their parchment to make way for a collection of Christian Palestinian Aramaic texts telling stories from the Old and New Testaments. The researchers thought that even earlier Christian texts were buried beneath the pages, but multispectral imaging revealed something more surprising: numbers stating, in degrees, the length and width of the constellation Corona Borealis and coordinates for the stars located at its farthest corners. The researchers published their findings Oct. 18 in the Journal for the History of Astronomy (opens in new tab) .

“I was very excited from the beginning,” study lead researcher Victor Gysembergh (opens in new tab) , a science historian at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) in Paris, told Nature (opens in new tab) . “It was immediately clear we had star coordinates.”

Related: Scientists unlock the ‘Cosmos’ on the Antikythera Mechanism, the world’s first computer

The researchers’ excitement grew when the precise coordinates enabled them to estimate the date when the coordinates were written down — roughly 129 B.C. when Hipparchus was a veteran astronomer puzzling over the night skies.

Historically referred to as the “father of scientific astronomy,” Hipparchus (circa 190 B.C. to 120 B.C.) spent much of his later years making astronomical observations from the island of Rhodes. Not much documentation of his life remains, but historical texts credit him with a number of impressive scientific advances, such as accurately modeling the motions of the sun and the moon; inventing a brightness scale to measure the stars; further developing trigonometry; and possibly inventing the astrolabe, a handheld disc-shaped device that can calculate the precise positions of the heavenly bodies.

In 134 B.C., Hipparchus saw something surprising in the night sky: In a patch of previously empty space, a new star had winked into existence.

The “movement of this star in its line of radiance led him to wonder whether this was a frequent occurrence, whether the stars that we think to be fixed are also in motion,” Pliny the Elder, a famed naturalist and military commander of the early Roman Empire, wrote in his book “Natural History.” “And consequently he did a bold thing, that would be reprehensible even for God — he dared to schedule the stars for posterity, and tick off the heavenly bodies by name in a list, devising machinery by means of which to indicate their several positions and magnitudes…”

St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, the sixth-century monastery where the map fragment was found. (Image credit: Jon Sellers / Alamy Stock Photo)

Hipparchus went on to catalog roughly 850 stars across the night sky, noting their precise locations and brightnesses. By comparing his complete star chart with more fragmentary measurements of individual stars taken by past astronomers, Hipparchus realized that the distant stars had appeared to move 2 degrees from their original positions.

He correctly concluded the reason for the shift in the stars’ apparent positions: Earth was slowly precessing, wobbling on its axis like a spinning top, at a rate of 1 degree every 72 years. Though references to Hipparchus’ famed catalog survive — notably engraved on the globe (opens in new tab) held atop the shoulders of a second-century Italian marble sculpture called the Farnese Atlas — it, and its copies, had been lost until now.

The researchers took 42 photographs of each of the nine pages across a broad range of wavelengths before scanning the photos with computer algorithms that picked out the text hidden underneath. Then, after reading the coordinates from the chart fragments, the scholars used the same idea of Earth’s planetary precession that had sprung from the chart to identify it. Reversing time, they wound the stars of the Corona Borealis back to the year when the luminaries shone in the sky at the exact spot the hidden writing described.

The date of the stars’ original recording was in 129 B.C., next the researchers had to find when the writing was done. By dating the nine folios according to palaeography — the study of identifying points in history by their distinct writing styles — the scholars placed them in the 5th or 6th Century A.D.; making them copies of Hipparchus’ catalog that were still being used more than 700 years later. RELATED STORIES —30 of the world’s most valuable treasures that are still missing

—Forged Galileo manuscript leads experts to controversial book he secretly wrote

—10 biggest historical mysteries that will probably never be solved

By comparing their wound-back night sky to a separate medieval Latin manuscript called Aratus Latinus, long believed to contain a partial copy of Hipparchus’ original catalog, the researchers confirmed that the Aratus manuscript’s coordinates for the constellations Draco, Ursa Major and Ursa Minor also landed on 129 B.C., providing compelling indirect evidence that the newfound fragment originated from the same source as the manuscript.

“The new fragment makes this much, much clearer,” Mathieu Ossendrijver (opens in new tab) , a historian of astronomy at the Free University of Berlin, told Nature. “This star catalog that has been hovering in the literature as an almost hypothetical thing has become very concrete.”

To continue the investigation, the researchers hope to improve their imaging techniques and scan more of the codex. Most of the manuscript’s 146 folios are currently owned by American billionaire and Hobby Lobby founder Steve Green and displayed in his Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C. In 2021, Hobby Lobby was forced to surrender 17,000 smuggled artifacts, originally looted from Iraq during the Iraq War, to federal authorities.

Aside from the codex itself, the researchers think additional pages from the star catalog may be hiding inside the more than 160 palimpsests at St. Catherine’s Monastery. Past efforts have already led to the discovery of previously unknown Greek medical texts, which include surgical instructions, recipes for drugs and guides to medicinal plants.

Editor’s note: Updated at 10 a.m. EDT to clarify that the Hipparchus’ star map is not the oldest star map on record, but the oldest complete star map on record. The honor of the oldest star map goes to an ancient Egyptian star map that was painted in a tomb about 3,500 years ago.