‘Private equity is now king’ for the ultra-rich, says Tiger 21, an exclusive club of investors

Michael Sonnenfeldt, Tiger 21

Scott Mlyn | CNBC

Private equity is currently “king” among members of Tiger 21 — a network of ultra-high net worth entrepreneurs and investors — according to its founder and chairman, Michael Sonnenfeldt.

The private equity industry had an especially tough 2022 after a decade-long bull run, but has picked up so far this year.

Sonnenfeldt told CNBC on Friday that Tiger 21 members, who collectively manage around $150 billion in assets, have increased their allocation to private equity threefold over the last decade, and see further opportunities amid an expected boom for companies exposed to AI and climate.

Most Tiger 21 members are entrepreneurs who have sold their companies and are now in the business of wealth preservation.

“Cash holdings are around 12%, they’ve trimmed down public equities, but our real estate came down a year or two ago because of rising interest rates, and private equity is now king — that’s where businesses are still scaling,” Sonnenfeldt said.

“Of course, the availability of credit makes it a little more difficult, but private equity is where our members are really focused because when you have basic businesses that are growing rapidly, that can outperform the market.”

Private equity has grown as a percentage of members’ portfolios from 10% to 30% over the last decade, Sonnenfeldt revealed, with venture capital comprising a larger portion than ever before.

“A lot of our members have seen that AI is a huge opportunity, climate is a huge opportunity and obviously the energy markets have done well, so our members really think that the fundamental growth over the long term is going to be favored,” he added.

According to a quarterly report from EY, private equity activity climbed 15% in the second quarter of 2023 versus the first, with total deal values hitting $114 billion on the back of a steep rise in Europe.

But not everyone is convinced that the optimism is justified. Dan Rasmussen, founder and chief investment officer at hedge fund Verdad Advisers, told CNBC on Friday that the industry is facing a “perfect storm” in the wake of sharp rises in interest rates and falling tech valuations.

“There are three big problems facing private equity. The first is that most of private equity is leveraged — about 60% net debt to enterprise value for the average buyout — and almost all of that debt is floating rate,” he said.

As interest rates have risen dramatically, the average interest costs for private equity firms have spiked. The median interest costs as a percentage of EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization) in the private equity and venture capital industry was 43% in 2022, whereas the median across companies on the S&P 500 index was 7%, according to Verdad Advisers.

“The second problem is private equity is 40%-plus exposed to the technology sector, technology valuations have been falling, and so as you see multiples coming down, that’s creating an additional problem,” Rasmussen said.

Cumulatively, this means the private equity industry has been buying companies at premium valuations versus public markets, with higher levels of debt.

Though some big tech companies with significant exposure to AI have seen valuations soar this year, dragging up the averages for the wider sector, smaller firms with higher leverage have generally not seen the same boon.

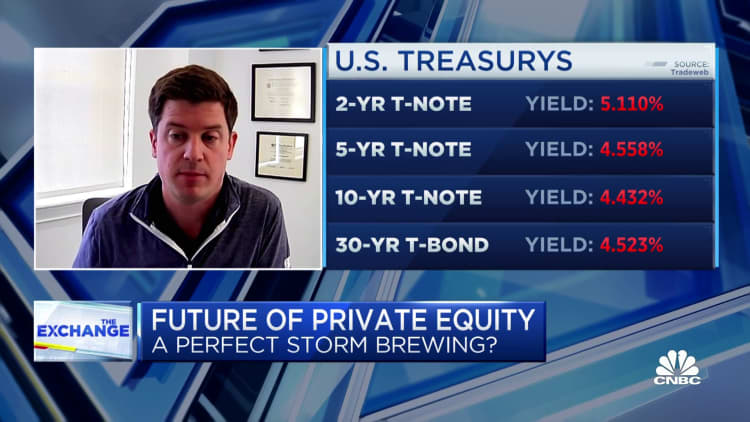

The U.S. Federal Reserve has increased interest rates by more than 500 basis points over the past 18 months, from a target range of 0.25-0.5% in March 2022 to 5.25-5.5% in July.

Though the Federal Open Market Committee opted this month to pause its rate hiking cycle, the central bank has suggested rates will stay higher for longer, which is typically negative for highly leveraged portions of the market targeting rapid growth.

“From a quantitative perspective, the fundamentals of sponsor-backed companies look frightening,” Rasmussen said in a research note earlier this year.

“Yet private equity remains the darling asset class of sophisticated investors, with many endowments and family offices nearing a 40% allocation. The financial fundamentals look far less attractive than one might expect, given such high level of enthusiasm.”